PHOTOGRAPH May/June Issue

|

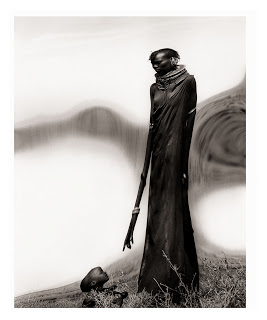

| African Future, 1988 |

by Lyle Rexer

After nearly two centuries of photography, after decades of scrutiny of photography’s colonizing impulse, Africa remains an imagined territory in western photography. But the images of otherness, fascination, and fear that have populated European and American encounters with a complex tapestry of societies have been countered not just by Africans themselves but by outsiders with other experiences and sympathies. And if these artists produce not “reality” but alternative myths, it simply goes to show that Africa is yet another place where imaginations are challenged and continuously reborn. Elisabeth Sunday’s work is inspired by tribal Africa, an Africa she has been visiting since the 1980s, and through which she seeks to celebrate the human. The product of a multi-cultural background, she looks to black Africa as tradition and future. Her love and fascination are captured in the cover image, African Future, taken during a visit among the Turkana in Kenya. This image, as well as a selection from her other African forays are on view at Throckmorton Fine Art in New York (May 2-July 6). She heightens the symbolic, emotional, and imaginative importance of the various peoples of Africa by using a mirror during her photo sessions. Her technique of elongating her subjects makes them more commanding, elevating them out of the documentary mode and emphasizing a characteristic mobility and dignity that she calls simply “grace.” As she remarks, “Photographing with mirrors allows me to see the world in a different light and capture some elements that remain hidden in straight photography. The use of elongation in indigenous and western art has long been an archetype for the unconscious. Following in this tradition, I use my mirror to shine into the internal deep spaces where we universally connect to something greater.” Adds Spencer Throckmorton, “Elisabeth Sunday is the granddaughter of Cleveland School painter Paul B. Travis, and she has become an important talent by devising her own distinctive artistry.” Like an intrepid photojournalist, Sunday has been to some of the most challenging locations, including Ethiopia, the Congo, and northern Mali, but the pictures she has brought back contradict the all too prevalent images of violence and political instability that fill contemporary media. Her series taken among the Akan fishermen off the coast of Ghana is a striking example. She poses the fishermen in intimate or balletic embraces with their catch, a kind of merging of the human and piscine. The arresting result suggests less a return to some animistic folklore than a forward-looking vision with an environmental message: only a sense of intimacy with the nonhuman realms we impact can provide a foundation for a saner, less destructive future.

Comments

Post a Comment